Who says you have the right to be intentional?

The Law of the Whole Person and what it implies

Everything that you read at this blog is based on three core principles: controlling the controllables, taking small steps within coherent systems, and taking responsibility for your own career. But lately, I’ve realized that there’s something deeper that needs to be addressed, and it’s the question: What gives you the right to pursue purpose in your work and life in the first place?

Everything here is predicated on the idea that you have agency and the right to exercise it, when it comes to how you manage your life. I think most people would agree that we do have both of these. But if you work in higher education any length of time, you will run into policies and people who seem aimed at the opposite. Do we actually have the right to pursue meaning and purpose in this business?

The Law of the Whole Person

As a mathematician, I think a lot about underlying axioms — statements that we accept as true without proof — and what can be deduced from them. Most axioms in mathematical systems, like Euclid’s Postulates, are grounded in human experience and nothing else. For example: A straight line segment can be drawn between any two distinct points. This is Euclid’s First Postulate and it offers no definition of “straight”, “line”, “drawn”, or “point” nor does it attempt to explain why this statement might be true. Everything just is, and the meanings of the terms and the truth of the postulate are supposed to be intuitively clear1.

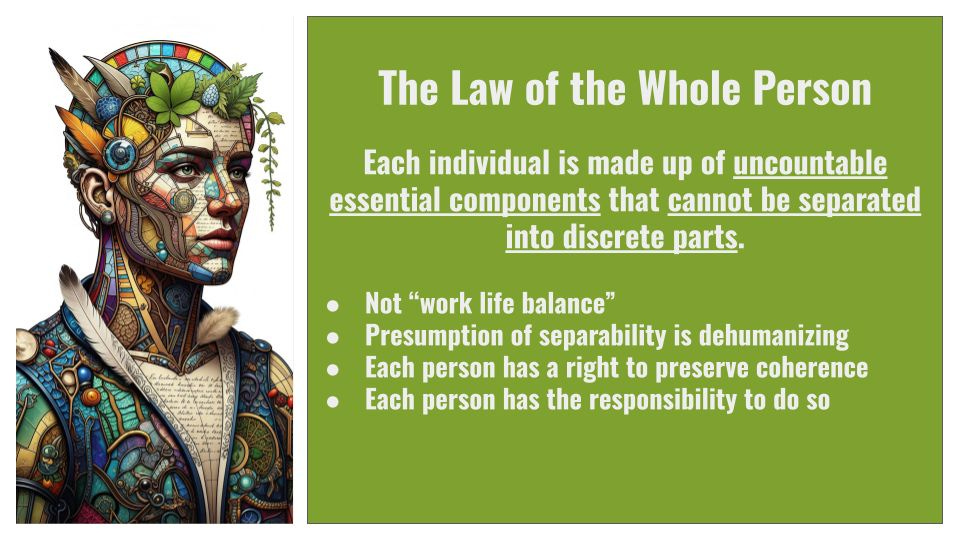

I firmly believe, as you probably do as well, that each of us does have the right to pursue meaning and purpose in our lives and work, and so “intentional academia” is not just an academic exercise. And the fundamental axiom that underlies that right is something I have come to call the Law of the Whole Person. It states:

Each person is made up of uncountable components that cannot be separated into discrete parts.

This sounds like geometry. It’s actually inspired by topology, my research area from back in the day. I think we all understand the idea of a “person”. Let me unpack the rest of the wording here:

Components: I do not say “parts” here, because the whole point of this axiom is that we don’t have “parts”. The meaning is closer to what David Allen and GTD call Areas of Focus. They are categories of thought and action that require regular review and maintenance — like projects, but unlike projects these are not “outcomes” that we desire. For example, your health is an area of focus. So is your scholarship; your teaching; your particular hobbies, etc.

Uncountable: In math, a countable set is one that can be put into one-to-one2 correspondence with the positive integers. What that means, is that you can label the elements of the set as the “first” one, the “second” one, and so on. An uncountable set is a set that cannot be so labelled. For example, the set of whole numbers 1 through 100 is countable. But the set of all numbers between 1 and 100, including the decimals and the irrational numbers like the square root of 2, are “uncountable”. There are not just infinitely many of them — the infinitude is so great that they cannot even be sequentially labelled.

Discrete: Not to be confused with the word “discreet”, discrete means “individually separate and distinct”. The opposite of discrete is “continuous” which implies a seamless flowing of one thing into another. Compare a color swatch of paint you might get from the hardware store, to a spectrum of colors you see in a rainbow. The former is discrete, the latter continuous.

So to say that each person is made up of “uncountable components that cannot be separated into discrete parts” means that our lives consist of areas of interest and focus, that are infinite in number and impossible to label or to separate fully. Each of us is a unified, whole person in a way that defies separating us out into parts.

The formulation of this idea is the third or fourth draft of it since I started pondering the idea several months ago. I understand this may sound like hippie buzzword-speak, so let me explain why I think the Law of the Whole Person, as stated here, is so profound, by looking at what it implies.

Implication #1: Higher horizons are real

In GTD practice there are six horizons of focus, which you can think of as “altitudes” from which you view your life and work. Horizon 0 is the “street level” and consists of your calendar entries and next actions. Horizon 1 is like the “second floor” and is made up of your projects. Likewise Horizon 2 is your areas of focus, Horizon 3 your one- to two-year objectives, Horizon 4 your three- to five-year vision, and finally Horizon 5 is your purpose and principles (encoded in a Life Plan).

Many higher education people operate as if there were no Horizons above 2. They are stuck in calendar events, to-do lists, and projects and never manage to see things at a higher level. Maybe if they are a department head or otherwise have a broad area of responsibility that is not a project, they spend time in Horizon 2 thinking. But otherwise, to have longer-term objectives and career goals often feels like a pipe dream. When I’ve discussed this with faculty, many of them express that they believe their job conditions constrain them from thinking at this level — like they need, but do not have, permission to do so.

The Law of the Whole Person says that everything that makes you, “you”, is part of a seamless system, no single part of which can be extricated from the others. It’s not like, say, a car — which, while a highly complex system, has parts that can be isolated, removed, and replaced without fundamentally altering the rest of the vehicle. Human complexity is categorically different: Everything is connected, and we cannot alter one part without fundamentally altering the others.

And what this means for higher horizons is that they, too, are connected in a vertical integration. If you touch one of the calendar entries or next actions on your list, it should reverberate in your 3-5 year goals and your Life Plan, if we are acting as whole people. And conversely, any serious consideration of our purpose and principles will deposit something in our 3-5 year vision, which then trickles down to 1-2 year goals, then to projects, and finally to the street-level next actions. It is all integrated — whole, in the same way we are.

So the Law of the Whole Person says that, yes, you do have the right (and the responsibility) to have a clearly defined purpose in life and to design your life in a way that preserves the unity stretching from that purpose all the way to your calendar. Because that’s just how humanity works.

Implication #2: There is no such thing as work-life balance

The notion of “work-life balance” presumes that there is a part of us that can be labelled “work” and another part that can be labelled “life”, and that these are separate and must be kept in “balance”. This is a well-intentioned and reasonable approximation to the truth. But it fails in real life because it is predicated on the idea of humans having “parts” that are discrete and separable, which the Law of the Whole Person denies.

Think about the act of walking. This takes a tremendous amount of actual balance. If you’ve raised kids and taught them to walk, or if you try to walk when you’re dizzy or “off balance”, you know what I mean. So how does an adult, physically capable human manage to just get up and walk? It’s not because we are consciously trying to keep our balance — carefully watching our feet, monitoring the force applied by one leg, and implementing the same amount of force with the other, while moving our arms in just the right amounts to counter-balance everything. Nobody would ever manage to walk successfully if it required that much computation3. Instead, when we were toddlers, the essential unity between our brains, inner ears, eyes, arms, and legs finally clicked and we just started walking. Today we don’t think about it, but simply do it, and trust in that whole-system unity to keep us upright.

Life ought to be like walking. We have overlapping components that focus variously on our teaching, scholarship, service, hobbies, friendships, family, and more and we don’t expect to create a pie chart of these where each one is a slice and the slices are in some kind of pleasing proportion to each other. There are no “slices”. We instead trust in our essential whole-system unity, which the Law of the Whole Person postulates, and just live.

My friend Josh Brake, who writes at The Absent Minded Professor Substack, wrote a lovely article a few years ago where he advocated for the term “coherence” rather than “balance”. I like that a lot. Josh is an engineer and used the concept of coherence from optics to motivate the idea, where light beams can be coherent while also interfering with each other — as these components of our lives often do — and asks whether our components are interfering constructively or destructively. Go read the whole thing.

Implication #3: Disunity is dehumanizing

If the Law of the Whole Person says that individuals are unified systems, then it follows that anything attempting to dis-unify a person is dehumanizing. Unfortunately, the world is full of people, systems, and policies that want to do exactly this, and higher education has more than its fair share of them. Perhaps the people or systems trying to dis-unify you don’t even realize that they’re doing it. But it doesn’t matter: It’s still dehumanizing, and it’s correct to call it out.

Sadly, there are almost as many examples of this form of dehumanization as there are people in higher education, but here is one that I’ve heard repeatedly: Requests (which are really more like commands) to do something for your department or school at times or places where you intend to have family or personal activities. (An extreme example of this was a colleague who was once asked by his department to hold office hours between 7:00pm and 10:00pm once a week.) If you’ve carefully considered a request like this, and it aligns with your higher horizons, and it doesn’t harm or inconvenience others, and you would like to do it, then it’s OK to go for it. But if it’s not something you care to do, and you are not contractually obligated to it, then the Law of the Whole Person says you have a right to say “no”.

You have that right because in this situation, the person giving the request — whether they realize it or not — is saying: I want you to separate out the “work” part of you, from the “personal life” part of you, and give your attention to the “work” part. But as I’ve argued, there are no “parts” according to the Law of the Whole Person. Asking you to think in terms of “parts” is dehumanizing.

Finally…

There is a corollary to all this which states something that makes a lot of people mad: We have not only the right to exist as whole people, we have the responsibility to advocate for ourselves to this effect. It’s a special form of being responsible for your own career4.

This means there is a lot of “saying no” that has to be done if we want to act as whole people. In the example above, you might be compelled to say “I can’t do what you are asking me to do because that’s time I spend with my kids. But I would love to discuss other ways to help.” That sounds reasonable, and it is, but it still might make the person giving the request angry because people who want something generally don’t like being told no, and some people are so immature that they can’t regulate that disappointment except to channel it into anger.

And yet, if you say “yes” to dehumanizing requests (again, even if the other person doesn’t intend to dehumanize you) just to avoid the negative emotions of others then two things happen. First, you earn a reputation as a person who will say “yes” even to the most dehumanizing requests, and people will start to take advantage. And second, you backslide on your humanity. For some, saying no to these kinds of requests seems to pose an unacceptable risk. But let me ask it this way: Would you rather have a job that’s “safe”, but in which you are less and less human every day — or would you rather be in a risky job situation where you are acting with integrity?

Nobody should be made to feel like they have to give away their humanity this way to keep their jobs, but this is real life, and nobody is coming to rescue us or do this work for us.

Etc.

I wrote this article using a workflow that I stumbled upon this summer that I now use regularly. I like to walk 3-4 miles each morning outside, for exercise and to get my brain going. I always have my phone with me in case of emergencies with the kids. When I walk, my mind tends to clear and I get good ideas. When this happens, I open up Google Keep on my phone where I have a pinned note called “Capture”, consisting of an empty checklist with one checkbox. Using the voice-to-text feature on the phone5, I’ll dictate that thought and have it turned into text in the note. Hit Enter, and it creates another checkbox; then just repeat this process until I’m out of ideas. Then, when home, I pull up the note on my computer, hide the checkboxes so it’s just text, then copy/paste into an Obsidian note where I can work on it later if needed. On one walk last week, I did detailed outlines of three different blog posts in a single 3-mile walk. My neighbors probably think I’m crazy, walking around and talking animatedly into my phone like I do, but it’s become the most productive “writing” time I’ve ever had.

Music: I played with a band last week that did a three-song mini-set of Ozzy Osbourne tunes, to commemorate his recent passing. One of those was “Crazy Train” and it reminded me of maybe my favorite YouTube video of all time, where two worlds collide.

The most common English translation actually states “To draw a straight line from any point to any point”; what I wrote captures the meaning of this somewhat elliptical (haha!) statement.

Trying to turn the act of walking into something computable in this way has been one of the hardest problems in the development of humanoid robots.

Or maybe, this basic concept flows from the Law of the Whole Person.

Android’s voice-to-text system has always been good but these days it is nearly perfect.

Wonderful post, Robert. Thank you. I too have been thinking in terms of coherence instead of balance - I look forward to reading Josh's post on this subject.