Questions about coherence

How do we act in alignment with what's most important?

Last week, I spoke (online) at a Lunch and Learn session for faculty at the University of Maine at Presque Isle. The talk was called “The Coherent Professor: Finding Productivity and Purpose in a Whole Faculty Life” and synthesized many of the themes you will read about here. I presented three principles for a coherent life within academia and applied it to a couple of real life examples, including email management. Here are the slides and here is a resource page that goes with them.

As usual, the Q&A session at the end was more interesting than the talk itself. I was given some questions to address before the talk began, by some folks who weren’t able to attend. I thought they were so compelling that I wanted to turn them into today’s post. So here they are, with my responses (that go into more detail than I had time for last week).

Advice for the young at heart (academically speaking)

The first question was: If you could go back and give your younger academic self one piece of advice about finding coherence and purpose, what would it be?

The youngest age where I think I even had an academic self, is 22, when I was a first-year Ph.D. student. I was a fish out of water: a rare Nashville-area native1 going to Vanderbilt, coming from an excellent but thoroughly non-elite state school (Tennessee Tech). My cohort represented some of the top graduates from universities not only from around the United States but also Europe and China. To this day, I’m certain my acceptance into the program was a clerical error.

I began the marathon of graduate school from about two miles behind the start line. That first year was back-breakingly hard. But it wasn’t complicated. For all the difficulty of graduate school, it is a simple life. I only had two jobs: study and get up to speed on research, and learn how to teach. Those two jobs are not trivial, but they are the only two I had. I wasn’t married, didn’t have kids, and had no expectation of having a life outside of school (I knew what I signed up for).

The advice that I would go back and give to myself is: This will not always be the case. As hard as it may seem now, you are playing life on “easy mode” if you only have two main things to worry about. So take advantage of the relative simplicity of your life, now, to build coherent systems that will scale up to what’s coming when you start your career.

There will be a day (I would tell myself) when you finish your PhD and start your career. The work at that point may or may not be as “hard”, but there will be an exponential jump in how much there is of it, and in the diversity of it. You’ll still be doing research and teaching, but you’re going to be teaching twice as much; serving on committees; doing service to your broader professional community; doing service to your campus and the community; meeting with more students; meeting with students who are not your students; dealing with internal politics; and more.

And by the way (I would continue to tell myself), you’re going to be moving to a new city where you don’t know anybody, so you’ll have to rebuild your personal life from scratch. You’ll have to manage your finances better because you will have a comma in your paycheck. You’ll have to start taking better care of your health because you’ll be getting older. And so on.

Right now (I would add to myself), while the work is hard, deciding what to work on is not hard. It’s either teaching or research. But later, you’re going to have so many things competing for your attention that it will be almost impossible to know what the right thing to do is, without a system. Everything will appear extremely urgent, so putting out fires isn’t a sustainable plan. So start now to decide what’s important to you and who you want to be, and build systems and workflows around it, so that when the floodgates open, you will have a systematic way of picking the things that are in your best interest, consistently and wisely. By the way, have you ever heard of this weird corporate concept called Getting Things Done?2

That’s what I would have told myself back in 1992. Whether I would have listened to myself is another question. I do remember going into my first job out of graduate school and having the exact experience mentioned above, and I wish I had had this advice back then.

In true academic form, the second question I got was actually three questions. I’m going to split these up into two parts.

Hitting a moving target

That second question, which was actually three questions, had two questions that went together well: How do we regularly show up for our most important work when that is defined and redefined multiple times over? How does this advice change for tenured, pre-tenured tenure-track, and non-tenure-track faculty?

This question got me thinking about a trip that my family and I took to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan over the summer. We were in the Keweenaw Peninsula area and we visited Copper Harbor, the northernmost town in Michigan. The town sits on the peninsula far out into the middle of Lake Superior. True to its name, there is a harbor there where freighters used to dock to receive copper ore that would ship out onto the Great Lakes and to points east.

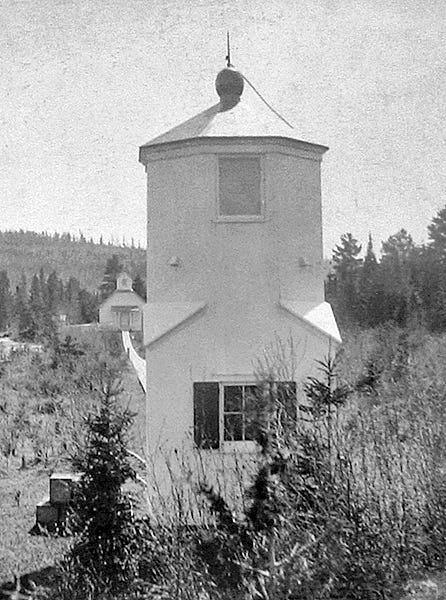

Lake Superior is a treacherous body of water for ships. Getting into the harbor safely is difficult when the weather is rough. So Copper Harbor has not one but two lighthouses: One on the shoreline, the other further inland and up an incline. (A photo of these is above.) By lining up these two lighthouses so that one of them appears to be vertically atop the other, a pilot can get a direct path of approach to get into the harbor safely.

The lesson I take away from this, is that to navigate volatile situations where everything is in constant flux, you need fixed points. Once you establish fixed points that do not change, you’re in a much better position to navigate the things that do because you can triangulate your position.

In order to consistently show up for your most important work, you first have to decide what actually is important at all. What are your core values in life? What are the primary roles that you play, and how do you want those to play out? In GTD language, we call this Horizon 5. If you’ve never actually taken a notebook or a Google Doc and written out the answers to those questions in a Life Plan, start there.

Without having a clear sense of these things, you’re going to find it difficult to show up for your most important work. Instead, just like my 22-year-old self, you will be simply doing the work that is the most urgent, not necessarily what is most important, and you will have no basis for making decisions about what to work on. You’ll be spending all your energy checking off boxes on somebody else’s to-do list. You may be physically present for your work, but there is no sense in which you have intellectually or emotionally “shown up”.

But if you know what your fixed points are, what your “lighthouses” are that you can line up to to chart a course for yourself, you may be surprised just how easy it is to navigate change.

Take generative artificial intelligence. This technology has thrown the entirety of higher education into a state of constant flux, and many people are, to put it mildly, really struggling with it. Following the Fall 2024 semester, where I had my first large-scale encounter with AI mediated academic dishonesty, I was definitely one of them. What’s helped me navigate the state of constant change is being crystal clear on what my fixed points are.

My core values are growth, humanity, temperance, and transcendence. And my primary roles in life include being an excellent teacher, among other things. This informs me about how to approach AI and how it’s changing higher education. For example, while I do want to mitigate the risks of cheating with AI, I also want to think about how I can harness it in my classes to enhance my students’ learning experiences, because that’s what being a teacher is all about. Therefore I don’t want to simply deny AI or “#resist” it as some are doing. And, because curiosity and growth matter to me, rather than avoid or mindlessly reject AI, I want to learn as much about AI as I possibly can. I’d be a sorry excuse for a learner if I didn’t.

Your core values and primary roles in life are probably different from mine and I’m not saying my way of thinking about AI or anything else is right. But I am definitely saying it’s in alignment with who I am as a person. And this how you show up to do your most important work every day.

I don’t think this is any different depending on your professional rank or employment status. Tenure or no, we all have an obligation to figure out who we are and then act in alignment with the answers. To do otherwise is to lose our humanity.

When all else fails…

The final question was perhaps the most provocative: What happens when or if we discover what is most important has nothing to do with our jobs in academia?

First of all, I think this happens more often than we think, especially as we get older. I think it’s very common, the more we engage with our lives, that we realize that what matters most to us isn’t found in our job description: Raising a family, attending to health, exploring faith, serving community, you name it. So it’s not an existential crisis. But it does mean we have decisions to make about how we respond.

In extreme situations, you might find that you have to pick one: either your Most Important Thing or your job. One or the other, but not both. For example, I had a pastor once who worked an ordinary 9-5 job, but then realized that becoming a priest was the most important thing he wanted to do, and since you cannot both be a Catholic priest and work in an accounting firm, he had to make a choice. If I were in that kind of situation, an all-or-nothing choice, the first thing I would do is sleep on it for a week. Because it’s very easy to become so enamored with a new idea that you feel like it’s worth quitting your job over. But if you put a little distance between you and that idea, you realize that it isn’t.

If you go through a period of discernment, including checking in with the people around you, then you would have to make a similar choice to the one my pastor did. Only you can make that choice. But I would say I have no judgment against people who leave academia to pursue things that they legitimately believe are more important for them, as long as they have a clear idea of what’s important to them and have gone through that period of discernment. In fact, I wish them the best and might be slightly jealous of them at times.

But most of the time, it’s not that extreme. You might spend quite a bit of time in academia and build a career, then realize that it’s no longer the most important thing to you. Something else is: raising a family, pursuing a side gig, starting a business, taking care of your health (or someone else’s). That “something else” may not require that you quit your job, but it does require that you reallocate your energy and time to fit the level of importance that you assign to it.

If that’s the case for you, then I have a few pieces of advice:

First of all, again, if you have not written out a Life Plan for yourself, where you’re very clear about your Horizon 5, do that. This is your map for the decisions you’re going to have to make next.

Second, honor the place of importance that your “something else” takes and just realize that it’s okay for your academic career to shift position so it’s no longer in first place. We should all really resist the temptation to be defined as human beings by the job that we hold.

Third, start making decisions in your job based on what you now realize about your “something else” as codified in your Life Plan. If your job is no longer the most important thing in your life, stop acting as if it were.

That third point is crucial. You cannot just decide that something is more important than your work: You have to alter your life and how you live it, so that you act in accordance with that decision.

For example, if you have kids and you come to believe that raising them and being present for them is more important than your academic job, then if your job asks you to work on nights and weekends – say no. And don’t just “say no” to requests, but build your life in such a way that your system, aligned with your life plan, automatically says no to choices that detract from the importance of raising your kids. For example, you can manage your email better so that you’re not answering messages all day. You can manage your course design and grading better and not grade on the weekends.

This point is really hard to hear because a lot of people will believe that their academic job is no longer the most important thing, but will be unwilling to die on that hill, discipline themselves to act, and accept the consequences which could potentially include unemployment. I fully understand that what I’m saying here is riskier for some people than it is for me. But I insist that if you truly believe that you have found something more important than your academic job, you will commit to that realization, no excuses and no apologies, and accept the risk.

So maybe this question goes with the other two after all. How do you handle the realization that the most important thing in your life is outside your job in academia? It usually requires that you allocate resources appropriately. And how do you know how to allocate your resources appropriately? You have to be crystal clear on your core values and your primary roles. You have to know what your fixed points are — the non-negotiables in your life that don’t change no matter what you discover.

Etc.

Podcast: I’m not really a podcast guy, but I found one that not only consistently delivers really excellent information about music, but also applies to life and to the classroom. It’s called The Bulletproof Musician, and it is published every Sunday. Most episodes are 7-9 minutes long (the sweet spot for podcast length in my view). The podcast is mainly about how to make musical practice better, but the applications are wide ranging to any sort of skill and they target exactly the sort of intentionality that I’m writing about here. As both a musician and as a teacher, I’m fascinated by this idea of deliberate practice, and I have really gleaned a lot from these episodes, so I highly recommend it.

Music: Speaking of AI, one of my favorite applications of this technology is taking songs and reinterpreting them in different genres. This is fast becoming a genre unto itself, and one of my favorite sources is the Fake Music YouTube channel. I have no idea what kind of technology stack this channel is using, but it’s incredible, and I will just let the results speak for themselves:

Dickson County born and raised.

David Allen’s book titled Getting Things Done, which popularized GTD, was not published until 2001, which was four years after I finished my PhD. However, he invented the system for himself in the 1980s and was giving corporate training sessions and coaching on it during the time that I was in graduate school (mid-90s). So it’s possible that I could have been introduced to it back then.