Fixing the missing piece of the Clarify process

A grand unified theory of academic email

After my last post about the Law of the Whole Person, I realized that I have not been telling you the whole truth about email and how to handle it. Now that the new academic year is underway, and probably you are already getting buried by emails, I wanted to offer what I think is a crucial update.

Previously, my recommended workflow for academic email is standard GTD stuff: Go to your inbox, start at the top, and process each item through the Clarify loop to determine what it means to you and what, if anything, you should do about it. This is still the process. But there is an important part that wasn’t explicitly mentioned, and it boils down to: Just because you can do something, doesn’t mean that you should. Taking this into account connects GTD practice with the Law of the Whole Person, to create what I like to think of as a grand unified theory of academic email.

What’s missing from the Clarify process

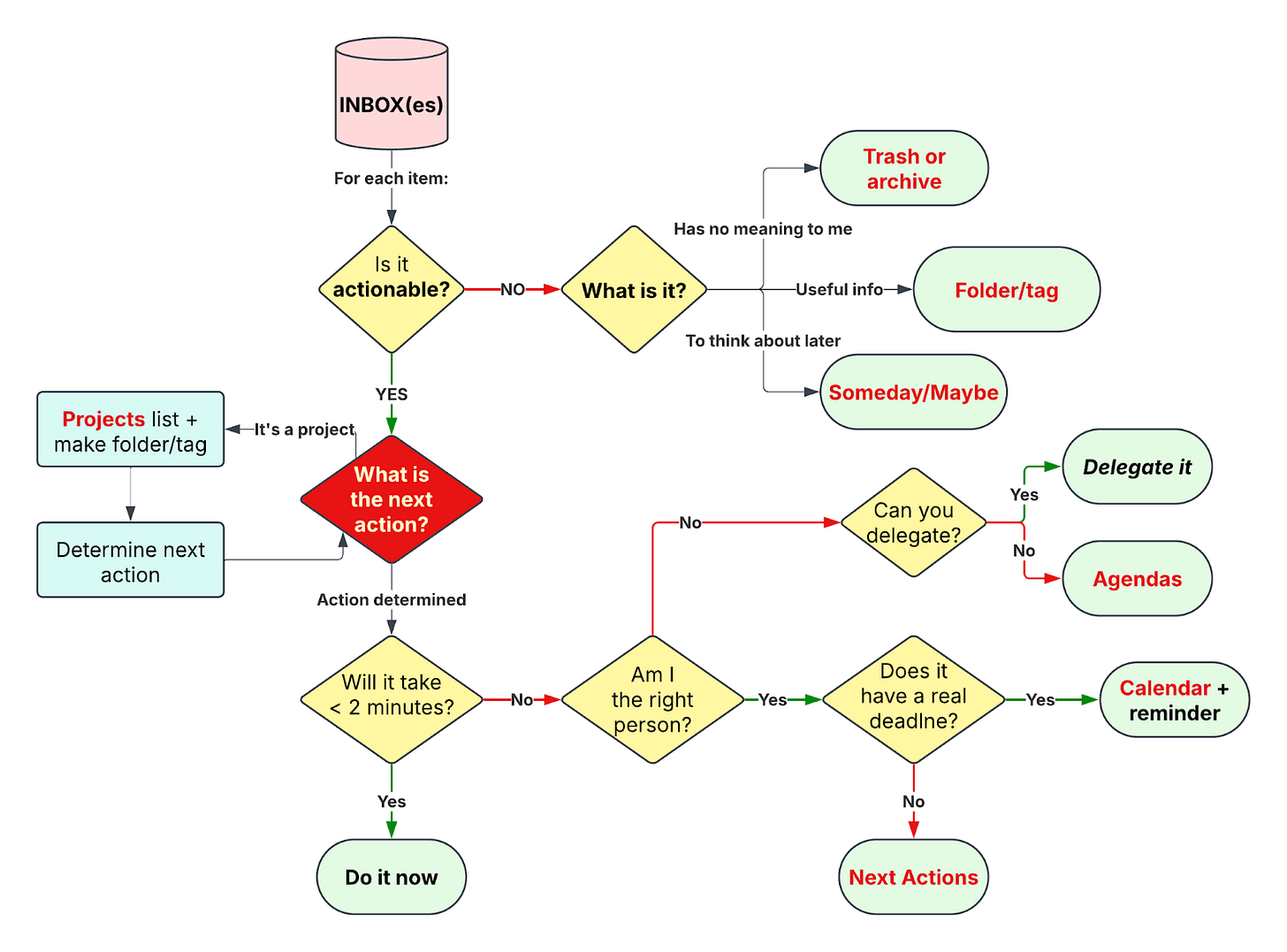

Let’s start with the basic Clarify process. This involves taking items that we have Captured over a small period of time and asking questions designed to find out what, if anything, each item means to us. Here is a slightly modified version of the standard GTD process that I made, specifically with academics in mind:

Keep an eye on that first yellow diamond, Is it actionable?

A large number of items that we capture (e.g. emails) have no actionable items in them. For me, the proportion of non-actionable items in my inboxes is usually over 80%1. They’re just information, or spam, or something I might get to someday — but not something that constitutes a here-and-now task. Of the remaining 20%, the Clarify process involves determining exactly what the action is (or, whether it’s not just one action but a project’s worth of them), whether it can be done right away, whether I am the proper person to do it (and if not, how to hand it off to the right person), and whether it has a deadline. Eventually every item, actionable or otherwise, ends up out of my inbox and in some part of my trusted system of lists, folders, and calendar.

But like I said, there’s something important missing, and it goes back to that first diamond.

Suppose something lands in your inbox that has a bona fide actionable item in it — for instance, a journal is asking you to review a paper. Running this item through the Clarify process leads you to determine what to do with it. But: What’s missing from this process is determining, for yourself, is whether or not you should be acting on this actionable item in the first place.

One of the key “aha” moments for me recently has been realizing that every Next Action in my system constitutes a commitment to completing that action in a reasonable time frame. When this light bulb switched on for me, I realized that over half of the items in my Next Actions list actually belonged on the Someday/Maybe list because I had no real commitment to completing them within 12 months and I was able to cut my Next Actions list down to size.

But framing Next Actions as commitments goes further than that. When we start viewing next actions as commitments, as I think we should, the question comes up — Why am I committing to these actions at all? And should I?

Back to that request to review the journal article: I’m on sabbatical right now and focusing solely on finishing my sabbatical project by the end of 2025. If I got that request from the journal, I would look at the email and see the actionable item there. But then I would not proceed through any part of the Clarify loop, because that action/project does not align with my Horizon 3 — my 1-2 year goals, chief among which are finishing my sabbatical project. I know with complete clarity that, although the item is actionable, my response is going to be a “no thanks”. And so there’s no point in wasting time figuring out what to do with this actionable item.

This clarity does not come from the Clarify process. Indeed it short-circuits the Clarify process and ends it before it really starts. The clarity instead comes from my higher horizons — which means it comes from the Law of the Whole Person. But, that Law does not make an explicit appearance in the Clarify process. But it should, and that’s what’s missing.

Fixing the flowchart

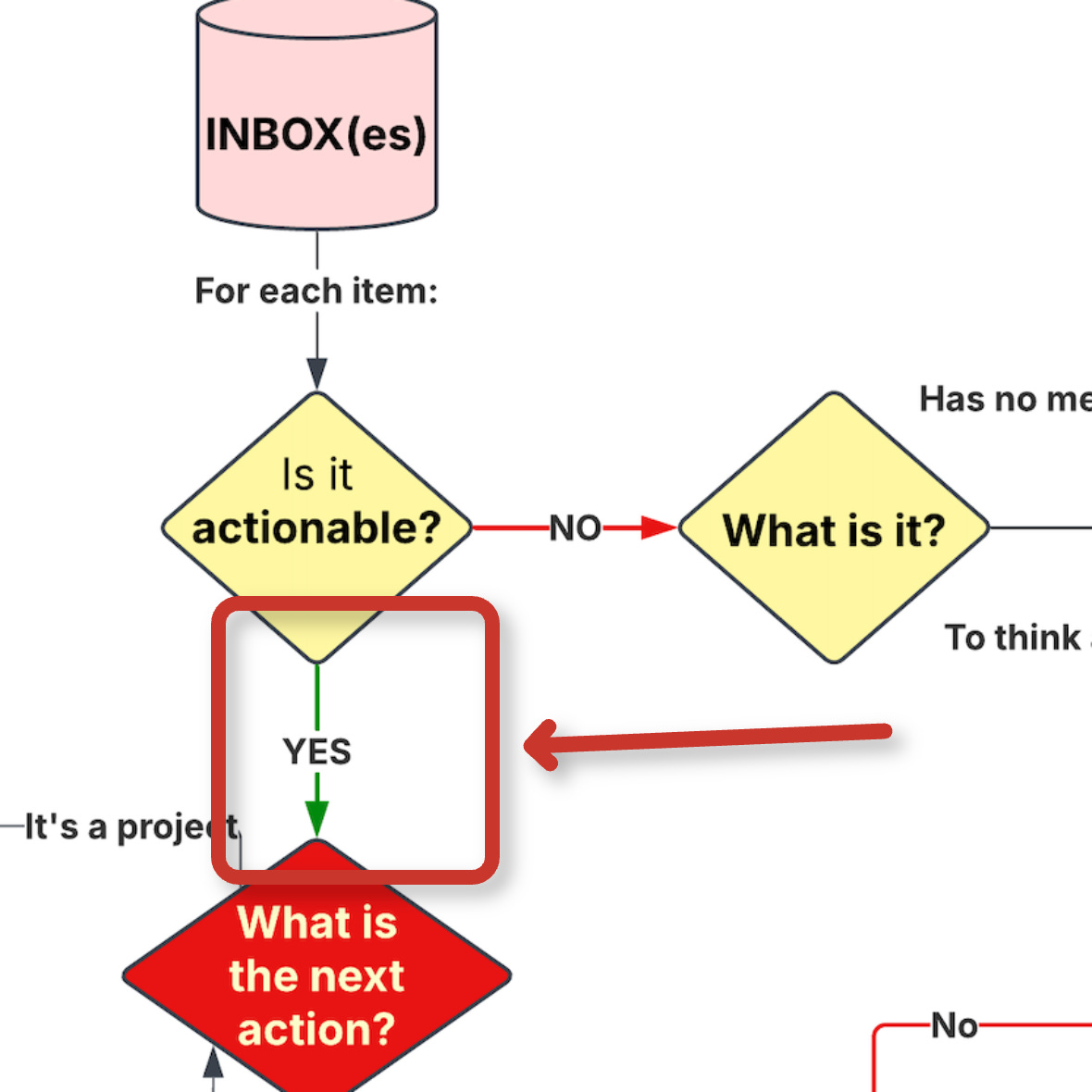

So, something needs to go right here in the flowchart:

There needs to be some kind of stop sign, or a filter, between the point where you decide whether an item is actionable, and the point where you start putting that action in the right place. Because based on your higher horizons, the right move on an actionable item might be not to act.

Here is what I think needs to go there.

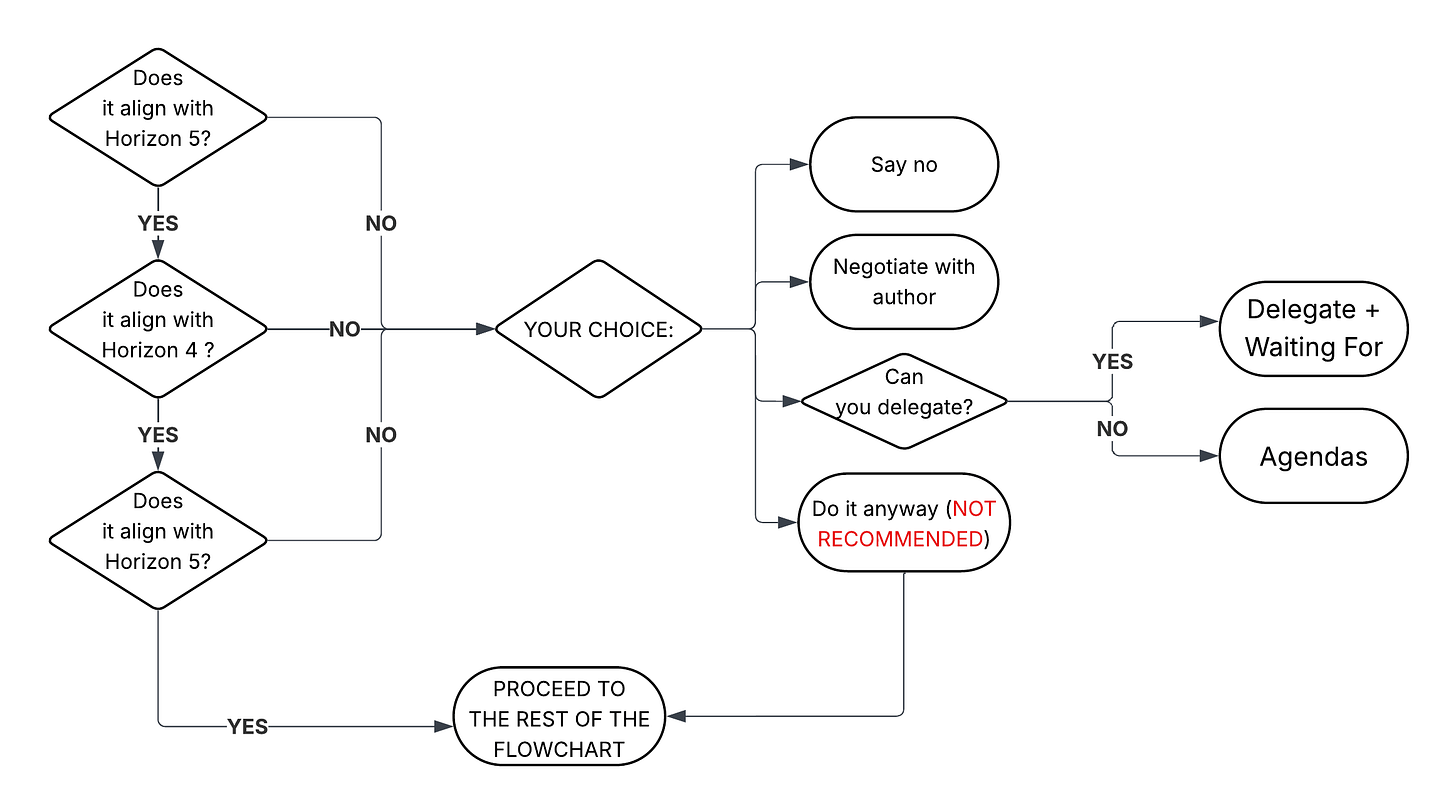

Once you determine that an item is actionable, there are three questions you must ask yourself, in this order, and be honest about the answers:

Does the item align with my Horizon 5 — principles and purpose?

If so, then does the item align with my Horizon 4 — my 3-5 year vision?

If so, then does the item align with my Horizon 3 — my 1-2 year goals?

If the answer to all three of these is “yes”, then you can move on to the rest of the flowchart, because not only is the item something that you can do (unless you decide later that you’re not the right person), it’s something that you should be doing because it lines up with your entire vertically-integrated existence — i.e. it supports the Law of the Whole Person.

But what if one of the answers is “no”? I have thought a lot about that question, and I think there are no clear flowchart-friendly directions on what to do. Instead, you have four options.

You can say “no”. The Law of the Whole Person implies that you have the right and responsibility to act as a whole person, with all your higher horizons integrated with your ground-level actions and projects, and nobody has the right to force you to do otherwise. In other words you have the right, as a human being, to say no to things that dis-integrate you. It’s not always easy or risk-free, and there are good and bad ways to do it. But you always have the right to do it, and often it’s the best course of action.

You can negotiate with the sender. That is, contact the person or group giving you the actionable item and explain your situation and see if there is some middle ground that can be reached. For example, if my department chair called up and asked me to sit in on a committee meeting, while I am on sabbatical, I would probably not just say no, but get back with her to explain that I am focused 100% on my sabbatical project right now which precludes committee meetings, but is there something I can do instead that could accomplish the same purpose as attending, which wouldn’t take time away from my project? Maybe there is. Or maybe there is no reason at all for me to attend, she was just asking anyway — in which case I would just say no.

You can try to have somebody else do it. In other words, delegate if if you have the authority, otherwise have a conversation with the “right” person if you don’t. This is pretty standard practice in academia; if someone asks me to give a talk, for example, but I can’t because of a schedule conflict, they’ll usually ask me for names of others to contact, and I’m happy to oblige. In the case of the committee meeting, once I figure out why my chair wants me there in the first place, I might check in with a colleague who isn’t on sabbatical and could do it instead, and gently ask them if they could. (Understanding that they, too, obey the Law of the Whole Person and have the right to say no.)

You can just do it anyway. You can look at the request and maybe see that it’s out of alignment with your higher horizons and still choose to take it on, for whatever reason. Maybe you feel it’s professionally dangerous to say no, negotiate, or delegate. Or maybe you just think you would enjoy it, despite it not serving your higher horizons. For example, I am currently writing a letter of recommendation for a colleague who is up for tenure, even though I supposedly laser-focused on my sabbatical project, because this colleague is a good friend and has helped me out in the past, and it’s not a huge lift to write them a letter. However: I don’t recommend “just doing it anyway” because it’s very easy to get into the habit of saying “yes” to things that aren’t aligned with your purpose and goals. Eventually you will lose the muscle memory of how to say “no”.

As I said, there isn’t really a flowchart-friendly binary decision process for knowing what to do with actionable items that don’t align with your higher horizons. You just have to use your judgment and some self-discipline on a case-by-case basis and accept that sometimes you’ll get that decision right and sometimes not.

The Grand Unified Theory

So, in the red box above, in between Is it actionable? and What is the next action?, put this:

EDIT: Yeah, I know that third diamond on the left is supposed to say “Horizon 3”. I’ll get around to fixing that… someday/maybe. 😅

I had hoped in this article to not just give you a new part to plug in to the original flowchart, but an entire updated flowchart that includes everything. But, I am cheap, and the free tier of the diagramming software I use puts a limit on the number of symbols I can use in a flowchart — and I maxed out that limit trying to make the complete picture.

Which brings up a couple of points I realized about email and its impact on our lives in academia:

If this Clarifying process, with its flowcharts and decision making logic, appears incredibly complex — it’s because it is incredibly complex. Properly deciding what to do with each open loop in each email we get, is a cognitively demanding task. With practice, the time requirement drops dramatically because this process becomes almost subconscious. But it’s never going to be effortless or easy. Remember, being intentional about life and work is about behavior change, which requires consistent effort over time.

Hopefully this will cause us all to step back and realize how much extra work we pile on each other when we send emails. Unpacking the decision making process here has really made me realize the importance of sending emails only when necessary, and when I do it the emails need to be short and sweet so this decision making process doesn’t consume the person I’m sending it to.

Etc.

Tools: The diagramming software I am using here is Lucidchart. I’ve used this tool for several years for drawing diagrams. (I have a possibly-weird fixation with flowcharts.) The free tier is probably enough for everyday use, although this article went beyond that. There is an educational discount for the full version and it integrates with Microsoft Office 365 if your campus does Microsoft things. It pairs pretty well with Lucidspark, an interactive whiteboard tool developed by the same company.

What I’m reading: Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise (2016, so not so “new” anymore) by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool. If you’ve been reading my stuff at Grading For Growth you know I’ve been thinking a lot about the concept of deliberate practice, and how it applies to alternative grading practices. But I’m also fascinated with the idea in my music pursuits, and everywhere else. At age 55 and trying to establish myself in the music scene, as well as trying to learn new things generally, I find a very hopeful message in this book, which is that simply engaging in deliberate practice consistently can create capacities for growth that you didn’t have before and it doesn’t matter so much how old you are or how much “talent” you were “given”.

Music: I’m a big fan of Rick Beato’s YouTube channel and learn something new every time I click on one of his videos. The one he posted yesterday was an all-time bait-and-switch situation — click on it for the inflammatory headline, stay for the master class on classical music and the achingly beautiful piece by Bach at the end.

An interesting application of the 80/20 rule.